Discussing the Three-Year Famine: Clarifying the Death Toll

Jun 29, 2024

When it comes to the Three-Year Famine, one of the most concerning topics for everyone is the death toll. Therefore, this series will first clarify the topic of “unnatural deaths.”

Table of Contents

- ★ What is “Unnatural Death”?

- ★ Official Statistics

- ★ What Does a Population Decrease of 10 Million in a Year Mean?

- ★ Comparing to the Eight-Year War of Resistance

- ★ Conclusion

★ What is “Unnatural Death”?

First, let’s clarify the concept of “unnatural death” to avoid any misunderstanding in the subsequent reading.

Whenever “unnatural deaths during the Great Famine” are mentioned, many people mistakenly believe that “unnatural death” simply means “starving to death.” In fact, starvation accounts for only a small proportion of “unnatural deaths.” Below, I will briefly explain the various situations of unnatural deaths during that period.

◇ Starvation

This is easy to understand, so I won’t elaborate further.

◇ Deaths Due to Malnutrition

During the Great Famine, due to severe food shortages, both adults and children generally suffered from malnutrition. Prolonged malnutrition led to various diseases (e.g., edema, stomach ulcers, hepatitis, tuberculosis, nephritis). Under the conditions at that time, diseases caused by malnutrition were impossible to treat. Why? Because the Great Famine mainly occurred in rural areas where medical conditions were already poor, and these diseases were too widespread for healthcare workers to address. So, a large portion of people slowly wasted away under the torment of these diseases. This situation likely accounted for the highest proportion of deaths.

◇ Deaths Due to Food Poisoning

In the face of severe food shortages, many farmers had to eat wild vegetables, grass roots, and tree bark to stave off hunger. Later on, when even grass roots and tree bark were gone, they started eating “Guanyin clay” (a type of inedible earth). It’s important to know that not all wild plants are edible; some are indigestible in large quantities, while others can cause poisoning. Eating too much “Guanyin clay,” which cannot be digested, was essentially suicide. Many people died this way.

◇ The Collapse of the Medical System Aggravated the First Two Causes

Remember, doctors and nurses are also human. During the Great Famine, they were starving just like everyone else. In some severely affected areas, medical institutions completely collapsed due to the large number of healthcare worker deaths. Even if some healthcare workers survived, they were too overwhelmed to care for others. As a result, many people, especially the elderly and children, died from untreated diseases.

◇ Unnatural Deaths Among Infants

In the face of severe malnutrition, many pregnant women gave birth to stillborn babies, and many miscarried. Please note: this situation is not reflected in population statistics. In addition to the situations mentioned above, some farmers, unable to feed multiple young children due to insufficient rations, would eliminate the younger ones (those just a few years old). If the child had not yet been registered, this was also not reflected in population statistics.

◇ Executions for Attempting to Escape Famine

In ancient times, when famine struck, many farmers would try to escape to relatively affluent provinces to beg for food. However, in socialist China, fleeing famine and begging were not allowed. In the Party’s eyes, fleeing famine and begging were old societal practices, which had no place in New China. How could New China tolerate such practices that tarnish its image? Therefore, in severely affected areas like Sichuan, Anhui, and Henan, many local officials mobilized militias to guard the roads, preventing farmers from fleeing. In some regions, those attempting to escape were executed on the spot. This barbaric behavior might seem unimaginable to many, but it is quite normal in a dictatorial regime. For example, in today’s North Korea, where famine is ongoing, many North Korean refugees try to escape to China. But if North Korean border guards catch them crossing the border, they shoot them on sight.

◇ Cannibalism

During the Great Famine, cases of cannibalism occurred in many provinces. If fleeing famine was a blemish on socialism, cannibalism was a disgrace to the cause. The Party could not tolerate such events. So, if cannibalism was discovered (whether it involved killing people for meat or eating the flesh of the deceased), the perpetrators were arrested and executed, often charged with “destruction of corpses.” If you don’t believe me, you can read another blog post of mine: Weekly Repost: Three Articles on the Great Famine. Some readers might think cannibalism was just a rare occurrence, but I will quote Liu Shaoqi’s conversation with Mao Zedong in the summer of 1962. Liu Shaoqi, visibly upset, said: “So many people have starved to death; history will record both you and me! Cannibalism will go down in the books!” (I’m not making this up; you can find Liu’s quote on Wikipedia). Just think about it—if cannibalism was only a rare occurrence, would Liu Shaoqi have specifically emphasized it? To add one last official source on cannibalism: the “Report on Special Cases of Cannibalism,” dated April 23, 1961, from the Anhui Provincial Public Security Department to the Anhui Provincial Party Committee. Here’s an excerpt:

Since 1959, there have been 1,289 cases of cannibalism, including 302 cases in nine counties of Fuyang Prefecture, 721 cases in 15 counties of Bengbu Prefecture, 55 cases in three counties of Wuhu Prefecture, eight cases in five counties of Lu’an Prefecture, two cases in two counties of Anqing Prefecture, and 201 cases in three counties of Hefei City. Most cases occurred in the winter of 1959 and the spring of 1960. In Xuancheng County, 28 of the 30 special cases occurred between October 1959 and February 1960; in Fengyang County of Bengbu Prefecture, 619 cases of cannibalism were reported in 1960, with 512 occurring in the first quarter, 105 in the second quarter, two in the third quarter, and only a few isolated cases in the fourth quarter.

◇ Suicide

Some people couldn’t bear the misery and chose to end their own lives. In some cases, entire families committed suicide together.

★ Official Statistics

So, how many people actually died unnaturally during those three years? There are many different claims. Some fifty-centers and Maoist zealots (such as Lin Zhexuan and Kong Qingdong) adamantly claim that no one starved to death, while some scholars conclude that the number of unnatural deaths exceeded 40 million (a vast difference). What’s the truth? Honestly, I don’t know the exact number (and I doubt anyone truly knows). However, we can make an educated estimate based on some analyses. To avoid interference from certain ignorant individuals and to preempt Maoist counterarguments, I will only use materials from official and authoritative sources in China.

◇ China Statistical Yearbook

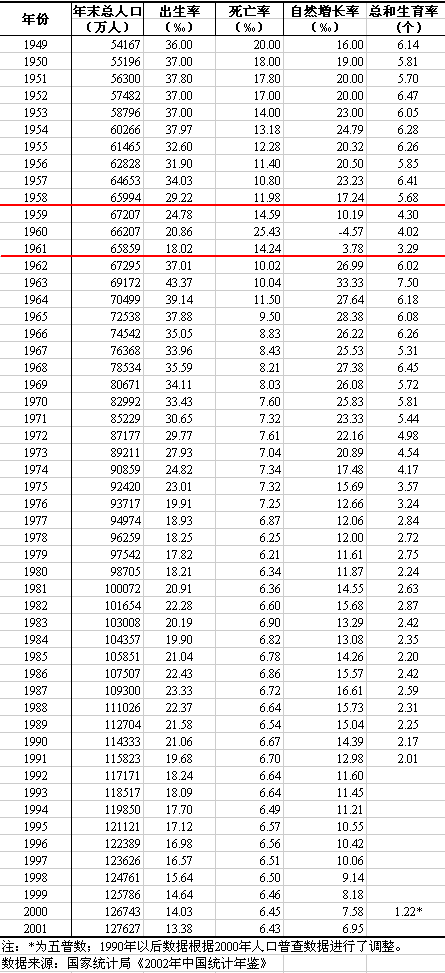

The China Statistical Yearbook is an authoritative publication released annually by the National Bureau of Statistics. On page 103 of the 1983 edition of the China Statistical Yearbook, you can find population data from 1949 to 1982. I’ve extracted the data for 1957-1965 for everyone to see.

| Year | Year-End Population (10,000s) | Birth Rate (‰) | Death Rate (‰) | Natural Growth Rate (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | 64653 | 34.03 | 10.80 | 23.23 |

| 1958 | 65994 | 29.22 | 11.98 | 17.24 |

| 1959 | 67207 | 24.78 | 14.59 | 10.19 |

| 1960 | 66207 | 20.86 | 25.43 | -4.57 |

| 1961 | 65859 | 18.02 | 14.24 | 3.78 |

| 1962 | 67295 | 37.01 | 10.02 | 26.99 |

| 1963 | 69172 | 43.37 | 10.04 | 33.33 |

| 1964 | 70499 | 39.14 | 11.50 | 27.64 |

| 1965 | 72538 | 37.88 | 9.50 | 28.38 |

As can be seen from the table above, from 1959 to 1961, the national population not only failed to grow but also clearly decreased. A simple calculation: between 1957 and 1959, the population grew by 25.54 million. From 1959 to 1961, the population decreased by 13.48 million. From 1961 to 1963, the population increased by 33.13 million. Apart from those three years, the population showed clear growth during all other periods.

To demonstrate that these numbers were not fabricated, I also provide an image from the official “China Population Information Network” (you can visit the official website here).

Some fifty-centers and Maoist zealots argue that the National Bureau of Statistics’ figures are suspect—pointing out that the population just so happens to have decreased by 10 million between 1959 and 1960, which seems too coincidental.

Honestly, I agree with them (it’s rare that I share a view with Maoists). I believe: these numbers were likely tampered with to **minimize the death toll**.

Everyone should be familiar with how China’s propaganda department operates—good news is heavily publicized, while bad news is downplayed. With such a serious disgrace as the Great Famine, the propaganda department would naturally try to cover it up a bit. Therefore, the National Bureau of Statistics’ figures likely downplay the severity of the famine, rather than revealing the true scale, and certainly not exaggerating it.

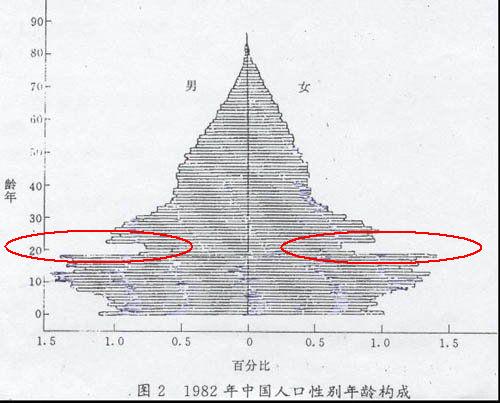

◇ 1982 National Census

The 1982 national census was the first national census conducted after the Cultural Revolution (it was more objective than the censuses during Mao’s era). Based on the results of the 1982 census, we can understand the age distribution of the national population at that time. I found an official statistical chart (see below):

From this chart, you can see a clear age gap (highlighted in red). The age gap corresponds to individuals aged 19 to 22 at the time, which coincides with the birth years during the Great Famine.

Some fifty-centers and Maoist zealots argue that this age gap was due to many farmers not having children during the Great Famine.

I believe that many farmers indeed reduced childbirth during the Great Famine. However, decreased birth rates are only one aspect of the age gap; the other is the extremely high infant mortality rate. The average mortality rate before and after the Great Famine was only about 1%, but the mortality rate in 1960 was 2.5%! A decrease in birth rates alone cannot explain such a “high mortality rate”!

◇ Official Authoritative Publications

Let’s look at some authoritative books published by the Party.

According to official statistics, in 1960 alone, the total national population decreased by 10 million.

From: The Seventy Years of the Chinese Communist Party, edited by Hu Sheng, published by the Central Party History Press, 1991, p. 381. (Hu Sheng was the Deputy Director of the Mao Zedong Works Editing Committee and the Deputy Director of the Central Committee Literature Research Office)

The number of unnatural deaths reached 40 million.

From: Mao Zedong Calls for “Rushing to Take the Exam in Beijing” - A Retrospective, by Liao Gailong, Yanhuang Chunqiu, 2000, Issue 3. (Liao Gailong was the Deputy Director of the Central Committee Party History Research Office and Deputy Editor-in-Chief of Xinhua News Agency)

According to conservative estimates, about 15 million people died of malnutrition.

From: Survival and Development, compiled by the National Conditions Analysis Research Group of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, published by Science Press, 1989, p. 39.

The number of deaths during the Three Difficult Years was two to three times higher than usual.

From: Contemporary China’s Population, edited by Xu Dixin, published by China Social Sciences Press, 1988, p. 74.

◇ Statements from Party Officials

If you think the authoritative publications are not convincing enough, let me cite some statements from high-ranking Party officials.

According to statistics, the total national population decreased by more than 10 million in 1960.

From: Reflections on Several Major Decisions and Events, Volume II, by Bo Yibo, published by the Central Party School Press, 1993, p. 873. (Bo Yibo was one of the “Eight Immortals” of the Party and a conservative official in the 1980s)

Wan Li recalled: “During the Three Difficult Years, there was widespread edema disease, and people starved to death. According to estimates, the so-called unnatural deaths in Anhui Province alone numbered three to four million.”

From: Reviewing the Course of China’s Rural Reform, by Tian Jiyun, China Economic Times, April 30, 1998. (Tian Jiyun and Wan Li both served as vice premiers in the 1980s and were reformist officials)

On April 14, 1961, Hu Qiaomu submitted a report to Mao Zedong regarding the problems with communal dining halls, in which he wrote:

Hu Qiaomu wrote to Mao Zedong: “I visited the Xiangxiang County, Hunan Province, and saw that the situation was very serious in the Nanxiang and Shijiang brigades of the Xincheng Commune, as well as in the Shuibei Brigade of the Chen Geng Commune. According to the county party committee, 30,000 people have died in the county over the past three years, with about 20,000 deaths occurring last year, and the situation was most serious at the end of last year.”

From: Central Committee’s Important Documents Issued by Mao Zedong - Hu Qiaomu’s Investigation of the Problems with Communal Dining Halls, Local History of Xiangxiang County (1949-2002), compiled by the Xiangxiang County Party History Group, Central Party History Press, 2004, p. 160. (Hu Qiaomu was a Party elder and Mao’s secretary at the time)

Former Secretary of the Chongqing Municipal Committee and Chairman of the Sichuan Provincial Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, Liao Bokang, recalled that during the Three Difficult Years, Sichuan Province recorded “10 million unnatural deaths,” and considering that the files did not fully reflect the number, he suggested adding another 2.5 million.

From: Contemporary Records of Major Events in Sichuan (Volume I), edited by the Editorial Committee of the Oral History of Contemporary China Series, Sichuan People’s Publishing House, 2005, p. 156.

These individuals are representative: they include reformist and conservative officials, as well as central and local officials.

★ What Does a Population Decrease of 10 Million in a Year Mean?

From the above introduction, it should be clear that the Party-state has officially admitted: the total national population decreased by 10 million in 1960. That’s sufficient! I’ll repeat: if the Party-state admits to 10 million, the actual number is only higher, not lower. Therefore, the number of unnatural deaths during those three years is certainly in the tens of millions. Whether it’s 20 million, 40 million, or even more, it hardly matters anymore. Let’s take a step back: even if the government didn’t alter the numbers, a population decrease of 10 million in a single year—do you realize how shocking that is? Take a look at the Population Statistics Table from earlier in this article. In the years before and after the Great Famine, the total national population increased by 14 million to 20 million per year. Yet in 1960, it decreased by 10 million. Just think about that.

★ Comparing to the Eight-Year War of Resistance

To leave a stronger impression, let’s compare this to the Eight-Year War of Resistance (I’ve made this comparison before in my blog post from last year, Who Is the Most Despicable? - A Letter to Anti-Japanese Zealots, but I’ll repeat it today). From 1937 to 1945, the Japanese couldn’t kill Chinese people at the rate of unnatural deaths during the Great Famine. Remember, for the Japanese, they were killing people of another ethnicity, while under Communist rule, they were killing their own people. 1937-1945 was wartime, while 1959-1960 was peacetime. Now, you see how amazing the Party is—without much effort, without wielding weapons, they easily killed tens of millions. Compared to our Party, the Japanese Imperial Army was child’s play! I have to admit, I am in awe of our Party’s efficiency in killing!

★ Conclusion

At the end of this article, I want to thank Lin Zhexuan. It was his outbursts of nonsense that sparked widespread discussion about reflecting on the Great Famine among netizens, which in turn prompted me to continue writing about that period in history. In the subsequent posts of this series, I will help analyze why the death toll was so high.

Author: 编程随想

Original post:

https://program-think.blogspot.com/2012/05/three-years-famine-1.html

Discussing the Three-Year Famine [3]: Debunking the “Soviet Debt Pressure” Lie

Table of Contents

- Clarifying the Sino-Soviet Split

- “Early Debt Repayment” Was Mao’s Initiative

- The Soviet Union Not Only Didn’t Pressure China But Also Offered Assistance

- Massive Grain Exports During the Famine

- Summary

In the previous post, I introduced how the Chinese government and Maoists have concealed the death toll of the Great Famine. At that time, Mao Zedong was at the helm, and with such a disgraceful event, he naturally wanted to save face. Not only did it tarnish his image, but as the top leader, Mao was undoubtedly responsible. To help Mao deflect blame, the government had to come up with excuses to shift responsibility and divert attention. Thus, the “natural disaster theory” and the “Soviet debt pressure” theory emerged. Today, I will focus on debunking the “Soviet debt pressure” lie.

★ Clarifying the Sino-Soviet Split

(Click to view details)

To debunk the "Soviet debt pressure" lie, we first need to understand the process of the Sino-Soviet split between these two Communist countries. Below is a brief timeline I've compiled, with annotations in parentheses. For a more detailed process, you can check Wikipedia here.

- February 1956: At the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party, Khrushchev delivered a secret report that fully repudiated Stalin. The report was not made public at the time and was only known to high-level members of the Soviet Communist Party and a few other Communist Party leaders. Mao Zedong was displeased with this report, which became a major source of anxiety for him—he feared posthumous criticism, much like Khrushchev had done to Stalin. This concern was a significant motivation behind Mao's initiation of the Cultural Revolution a decade later, with the aim of "exposing the Khrushchevs around us" (Mao's exact words, familiar to those who lived through the Cultural Revolution).

- Early 1958: The Soviet Union proposed forming a joint fleet with China and establishing a long-wave radio station in Chinese ports. Mao rejected the proposal.

- June 1959: The Soviet Union ceased providing nuclear technology to China.

- April 1960: The Chinese Communist Party published three articles, including "Long Live Leninism," ostensibly criticizing Yugoslavia for revisionism but implicitly targeting the Soviet Union.

- June 1960: At a conference of Communist Parties in Bucharest, the Soviet Union distributed written documents to refute China's three articles (the Sino-Soviet conflict became public, but the disagreement remained theoretical at this point).

- July 16, 1960: The Soviet Union officially announced the withdrawal of all Soviet experts from China, ending its assistance (from this day forward, most Chinese citizens became aware of the Sino-Soviet split).

- October 1961: At the 22nd Congress of the Soviet Communist Party, Zhou Enlai led a Chinese delegation to attend (Zhou's attendance indicated that Sino-Soviet relations had not completely collapsed). At the congress, Khrushchev criticized Stalin again and proposed exhuming Stalin's body from its crystal coffin and cremating it—a move that deeply upset Mao. Khrushchev followed through on his promise and later exhumed Stalin's body. Additionally, the Soviet Communist Party criticized Albania at the congress, leading Zhou's delegation to walk out in protest (Albania was China's closest ally in the Communist bloc at the time).

- July 14, 1963: The Soviet Communist Party published an open letter to all levels of the Soviet Party organization and members, openly criticizing the Chinese Communist Party.

- September 6, 1963 - July 14, 1964: Mao personally directed his literary staff to publish nine articles criticizing the Soviet Communist Party, known as the "Nine Commentaries on the Soviet Communist Party" (the Sino-Soviet relationship reached its nadir as the two parties began openly denouncing each other).

- March 1969: The two sides engaged in a military conflict at Zhenbao Island in Northeast China.

- August 1969: The two sides engaged in a military conflict at Tielieketi in Xinjiang.

★ “Early Debt Repayment” Was Mao’s Initiative

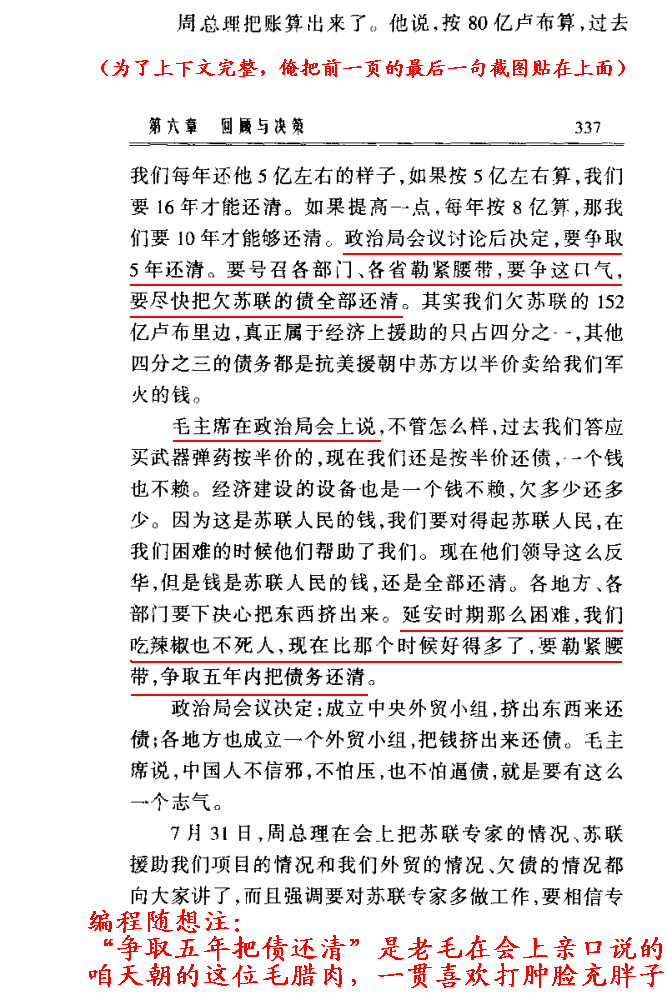

Although the Soviet Union withdrew its experts and ended its aid in 1960, it did not force China to repay its debts early. Instead, it was Mao himself who proposed repaying the debt within five years.

To avoid accusations of fabrication from Maoists and fifty-centers, I have found an electronic version of the book Ten Years of Debate: A Memoir of Sino-Soviet Relations from 1956 to 1966 as evidence (you can download it from my online archive). The author, Wu Lengxi, held numerous prominent positions, including President of Xinhua News Agency, Editor-in-Chief of People’s Daily, Deputy Minister of the Propaganda Department, and Deputy Director of the Mao Zedong Works Editing Committee… Just look at those titles—he was a highly authoritative figure within the Party. Additionally, the book was published by the Central Party Literature Press, an official publishing house.

Below is a screenshot of page 337 of the book, with the relevant text highlighted.

1960 was the most severe year of the Great Famine. Why did Mao insist on repaying the debt early, despite the country’s economic difficulties? The main reason lies in Mao’s competitive nature and his obsession with face-saving. At that time, the Chinese and Soviet Communist Parties had already begun theoretical debates. Mao felt that if China still owed money to the Soviet Union during these debates, it would make him appear weak and lacking in confidence. Therefore, Mao disregarded the suffering of the people and insisted on repaying the debt early.

★ The Soviet Union Not Only Didn’t Pressure China But Also Offered Assistance

As the timeline of the Sino-Soviet split indicates, the relationship between China and the Soviet Union did not completely deteriorate until after July 1963. Although the Soviet Union withdrew its experts and ended its aid in 1960, the relationship had not yet broken down entirely. During the Great Famine, the Soviets, out of camaraderie within the socialist camp, provided some assistance to China in addressing its food shortages.

To demonstrate the Soviet Union’s support, I quote from a speech given by Ye Jizhuang, Minister of Foreign Trade, during his visit to the Soviet Union in April 1961 (the speech was published in the People’s Daily on April 10, 1961):

In the process of restoring the national economy and building socialism, the Soviet Union provided us with enormous assistance. Due to severe natural disasters in recent years, the supply of goods to the Soviet Union in 1960 fell significantly short. In 1961, many goods could not be exported or had to be exported in reduced quantities, causing some difficulties for the Soviet Union. However, our Soviet comrades showed cooperative and brotherly understanding in this matter. The Soviet government agreed to allow us to repay the arrears from our 1960 trade over the next five years without interest. Additionally, they offered to lend us 500,000 tons of sugar without interest, to be repaid later with an equivalent quantity. We believe that this was a significant help and support in overcoming our temporary difficulties.

From the above description, it should be clear that the Soviet Union was not only not taking advantage of the situation but also helping China out.

★ Massive Grain Exports During the Famine

Finally, let me reveal something: during the three years of the Great Famine, despite the fact that tens of millions of people were starving to death domestically, the Chinese government voluntarily exported large quantities of grain and other agricultural products. Much of this exported grain was used to provide free aid to China’s smaller allies (e.g., Pakistan, Albania, Laos…).

I checked the China Statistical Yearbook published by the National Bureau of Statistics. In the report delivered by Zhou Enlai at the Third Session of the First National People’s Congress in 1964, Zhou stated the following (the full report can be found on the official website here):

During this period, not only did we not borrow a single penny of foreign debt, but we also repaid almost all of our past debts. We have repaid 1.39 billion new rubles out of the 1.406 billion new rubles in loans and interest owed to the Soviet Union, leaving only a small balance of 17 million new rubles, which we have proposed to repay entirely this year using part of our trade surplus with the Soviet Union. In addition, we have provided financial and material support far greater than the amount of debt repaid during this period to support socialist and nationalist countries.

Additionally, I reviewed the export statistics from the China Statistical Yearbook (1983 edition) published by the National Bureau of Statistics, which includes detailed export statistics by product category for those years. Below are screenshots from pages 422-424 of the statistical yearbook. To make it easier for readers to understand, I added prominent annotations.

_01.png)

_02.png)

_03.png)

Since the above lists are categorized by product, there are more than ten tables in total. Due to space constraints, I won’t list them all. Interested readers can check the China Statistical Yearbook for more details. After reviewing the agricultural export data during the Great Famine, what are your thoughts? I am reminded of a famous saying from the Qing Dynasty: “Rather give to foreigners than to domestic slaves.” Clearly, the long-standing national policy of our Glorious, Correct, and Just Party has been to let their own people starve to death rather than give grain to other nations.

★ Summary

Based on the evidence presented above, the “Soviet debt pressure” story is entirely fabricated. If anyone was pressuring for debt repayment, it was Mao pressuring the Chinese people to repay the Soviet Union’s debt early.

Finally, let me briefly explain the origin of the “Soviet debt pressure” lie. Refer to the earlier timeline of the Sino-Soviet split. By the late 1960s, China and the Soviet Union had become adversaries (having fought several skirmishes along the border). At that time, Sino-Soviet relations were worse than Sino-U.S. relations. In this context, China’s propaganda department attributed half of the responsibility for the Great Famine to the Soviet Union. This move was a stroke of genius—it not only demonized the Soviet Union but also helped the Chinese leadership, especially Mao, deflect blame. As for the other half of the blame, the propaganda department attributed it to “natural disasters.” Therefore, in the next post of this series, I will focus on debunking the “natural disaster” lie.

Original post:

https://program-think.blogspot.com/2012/08/three-years-famine-3.html

– This text was translated by AI. –